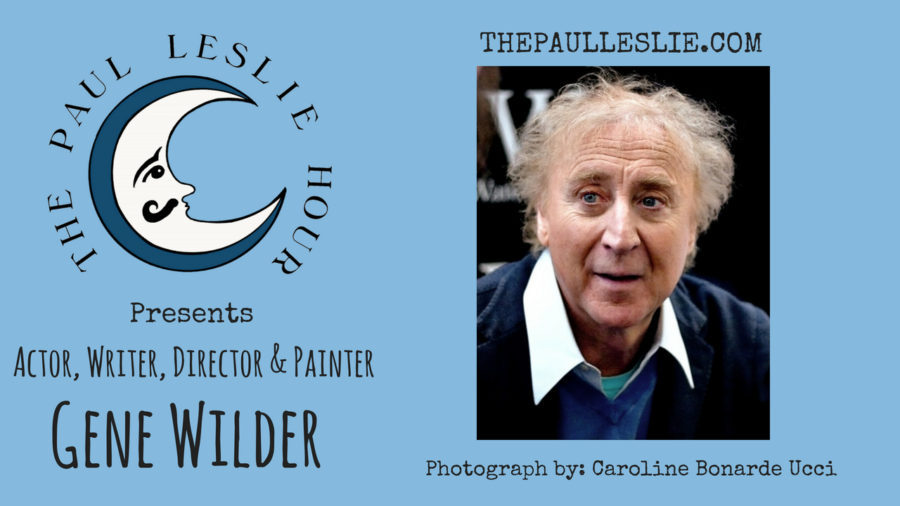

Gene Wilder was born June 11, 1933. He was an iconic actor and director, but also a writer and painter. He passed away on August 29, 2016 and today would have been his birthday. This was one of my all-time favorite interviews.

Or Listen on YouTube:

Here is the original introduction written by Daniel Buckner and a transcript follows.

Delve into the mind of a quiet genius. Within it you will find an entire world of thought, creativity, and power. How true that is for the mind of Gene Wilder! We all know him by his roles in the films Willy Wonka and The Chocolate Factory, Blazing Saddles and Young Frankenstein among a host of others. However, these are but a few colors on the creative pallet of Gene Wilder’s career.Gene is an accomplished stage actor, has written for the screen and directed. He has authored several books: Kiss Me Like a Stranger, My French Whore, The Woman Who Wouldn’t and Something To Remember You By. These works reflect the same genius and talent manifested in Wilder’s screen writing, directing and acting.Gene Wilder has set the professional standards which aspiring artists still endeavor to reach over fifty years after his debut. As great as his mind is, he is also a man with a golden heart. He is a warrior in the fight against ovarian cancer, establishing Gilda’s Club with Joanna Bull and Joel Siegel. Such a heart and mind merits the attention of the world. That is the why we hope that you will share in the privilege of hearing from the great…the incomparable Gene Wilder.

Young Frankenstein.